For the last two weeks I have been so busy collecting materials for The Elements Unearthed project that I haven’t had time to write any blog entries. My daughter flew in from Utah to visit us in Philadelphia and she has helped me videotape and photograph some local mines and minerals. I’ve collected materials for four new podcast episodes, including anthracite coal mining in Pennsylvania, minerals and gems of the Smithsonian, zinc mining in New Jersey, and the history of the Periodic Table of the Elements. Let’s take a look at samples from each of these future episodes:

Lackawanna Coal Mine:

On Thursday, August 6 we traveled to Scranton, PA and visited the Lackawanna Coal Mine and the Anthracite Heritage Museum. The tour into the mine lasts about an hour, and our guide, Roger Beatty, was informative and funny. He allowed us to attach a wireless microphone system to him, which we then fed into my small HD camera so that we could have good audio regardless of where we were standing underground. The video itself is pretty good for being hand-held and in the semi-darkness of a coal mine. The coal here in northeastern Pennsylvania is anthracite or metamorphic coal and has to be mined using hard rock techniques. The veins that were mined and which underlie the Lackawanna Valley (Scranton) range from 8-10 feet seems to 18 inches tall. These thin “monkey” veins had to be mined on all fours, usually at a steep incline. Since the coal seems are broad and stretch for miles in all directions, the technique for mining is to create a grid of galleries and cross-cuts with pillars of coal left in place in between to support the weight of the rock above. Some galleries are made wider as gangways for cart tracks and ventilation; once the edge of the mine property is reached, the mining procedes backwards as the pillars are robbed. If too much coal is mined, the entire area may collapse.

In the Wyoming Valley nearby, unsafe mining techniques led to a stope in the Knox Mine being cut only three feet under the muddy bottom of the Susquehanna River, and on Jan. 22, 1959 the weight of the water punched a hole into the mine and eventually flooded all the mines in the valley and drowned 12 miners. Anthracite coal was already having hard economic times when this disaster led to the closing of most of the anthracite mines in Pennsylvania. It is estimated that if the mines could be pumped out, there still remaines over 8 billion tons of anthracite coal in Pennsylvania alone.

Centralia, PA:

In addition to roof collapse and mine flooding, coal mines can have other hazards. Over 30,000 men died in the anthracite mines from the time records were kept in the 1870s until now. But in one case, no one died except a town.

In 1962 the coal town of Centralia, PA was a prosperous village near Ashland and about ten miles from Frackville. Then burning trash in an abandoned open pit mine set a seam of coal on fire. When the fire was put out on the surface, the coal continued to burn underground, and repeated efforts to extinguish the slowly burning seams have all failed. The fire has gradually spread and the fumes (sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, etc.) were deemed too hazardous for the residents to stay, so the town has been evacuated and the houses moved into the next valley (except for a few die-hards who refuse to leave).

Now you can visit the town, as we did on our way back to Philadelphia, and see roads that lead nowhere and a hillside near the cemetary that is still smoldering. In one small mound we could see several vents with fumes wafting out, so we took our video equipment over and documented it. We found that you certainly don’t want to breathe the fumes! I tried to pick up a few pieces of slate mixed in with the gray coal to see what was underneath, and the ground was hot to the touch. Once the slate was pulled out, a layer of coal ash could be seen in the hole left behind. After 47 years, Centralia is still on fire.

Minerals and Gems at the Museum of Natural History:

We visited Washington, D.C. on August 7-9 and I spent some time in the Natural History Museum photographing the rocks, minerals, and gems. The Smithsonian has such an extensive collection that all the specimens are amazing; they have enough to even show displays of unusual crystals and mineral colors and crystal shapes. They also have samples of many famous meteorites, of all types of rocks from the rock cycle, examples of deposition and erosion, families of minerals (such as sulfates and silicates) on display, and, of course, some of the most famous gemstones in the world, including the Hope Diamond. Although the Hope is certainly nice, I personally like the emeralds better.

I have often been accused of having rocks in my head, and all the photos I took (I filled up about 3.5 GB of disc space) certainly proves that at least I have rocks on my mind.

Sterling Hill Zinc Mine:

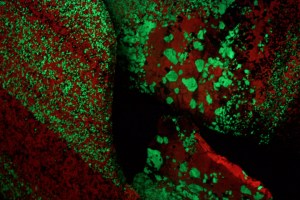

On Wednesday, Aug. 12 we drove to northern New Jersey about 30 miles due west of New York City to the town of Ogdensburg where the Sterling Hill Zinc Mine is located. Operations shut down here in 1986 and the mine facilities have been turned into a museum of mining artifacts and a world-class mineral exhibit, including fluorescent zinc minerals such as the green-glowing willemite seen here. They have a display of the elements of the periodic table, and even have a sample of ore from the Tintic Mining District in Utah (the Mammoth mine).

After touring the museum, we spent 90 minutes touring the mine. The zinc was deposited through igneous activity in ancient sea floor limestone deposits, which were then uplifted and metamorphosed into marble with the zinc as veins running through the marble.

The Periodic Table:

In addition to all of this, Chemical Heritage Foundation hosted the International Society of the Philosophy of Chemistry (ISPC) annual symposium Aug. 13-15 and I attended some of the sessions. Although some of the philosophy was beyond the scope of this project, there were some sessions that tied in directly, including the history and philosophy of the periodic system. Dr. Eric Scerri, a noted authority on the history and structure of the periodic table, presented at the conference and consented to be interviewed by me.

He is the author of the book: The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance (2007, Oxford University Press), and I asked him a series of questions about the discoveries and knowledge that led to Mendeleev’s successful table and some of the issues that still remain, such as whether or not the periodic system can be fully deduced from quantum mechanics (a central point of discussion at the symposium). In addition to Dr. Scerri’s interview, I hope to visit several installations of periodic tables on my way back to Utah along with the one here at CHF and the one at the zinc mine and have enough materials to create several podcast episodes specifically on the periodic table.

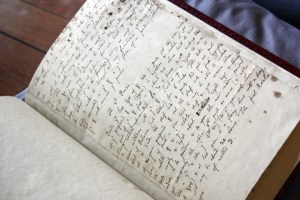

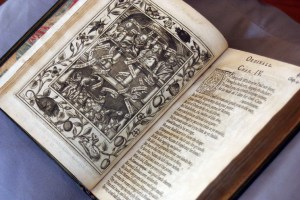

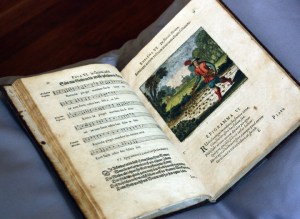

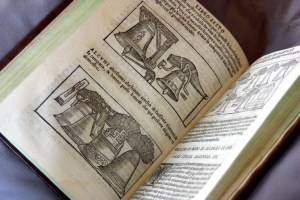

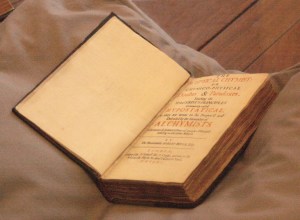

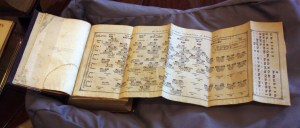

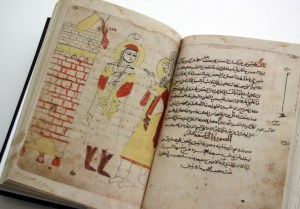

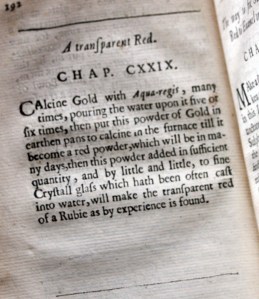

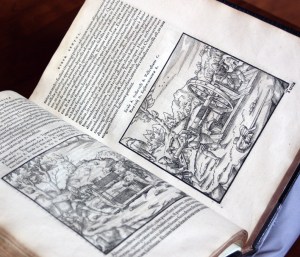

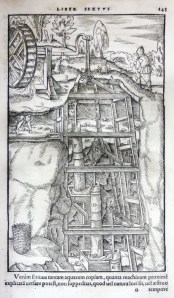

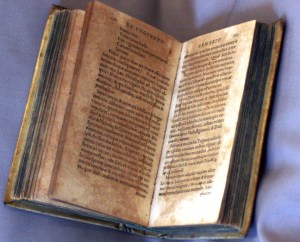

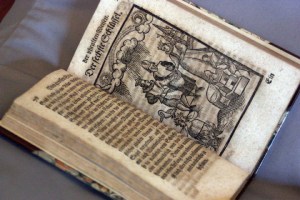

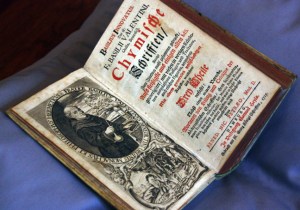

Couple of final notes: As part of the symposium, one of our curators, Jim Voelkel, put out some of the rarer of our rare books and this time included a hand-written manuscript of Issac Newton’s, with notes on his alchemical experiments. I finally got to see it, and here is a photo of it.

One of my goals this summer was to gain at least 2000 images related to this project; since I have bought my new camera in May, I have taken almost 7000 images, over half of which are for The Elements Unearthed. I am looking forward to using them in upcoming episodes. I certainly feel I have succeeded in my goals so far at CHF, and now have two more final weeks to finish up my research, then drive back to Utah. On the way, I am planning on a few more stops such as a lead mine in Missouri and a gold mine in Colorado. By the time I return to Utah, my students and I will have collected video and photos that can be used for at least 30 podcast episodes on subjects ranging from beryllium to zinc. I’ll have some video samples of the coal and zinc mines and Dr. Scerri’s interview next time, and some final podcast episodes ready by August 29.