The following posts will detail my expedition to document the history of mining in Colorado. Funds for this trip were provided through Teachers Without Borders and the MIT BLOSSOMS project, sponsors of the What If Prize competition.

I began my journey on Monday, July 9. After getting everything packed in my Dodge Grand Caravan mini-van, I left my home in Orem, Utah about 11:00 and traveled south on I-15 to Spanish Fork, then east on U.S. 6 through Spanish Fork Canyon. I stopped to take a few photos of the Thistle mudslide and what’s left of the town of Thistle itself. In the fall of 1982, after two weeks of constant rain brought in by a tropical storm, a large section of the canyon wall gave way and slid into the bottom, damning the river and flooding the small town of Thistle. The main Denver and Rio Grande Railroad had to build tunnels through the slide and U.S. 6 had to be routed around the disaster. Now, thirty years later, the slope is still unstable but is beginning to get a re-growth of oak brush, but no pine trees yet.

The Western Mining and Railroad Museum in Helper, Utah

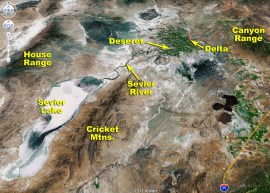

Coming down the east side of Price Canyon, I stopped at a road cut where a nice coal seam is visible. This one is too thin to be economically mined, but it gives an idea how the coal is interbedded with sandstone and shale layers. The coal began as swamps during the Jurassic Period that ringed a shallow inland sea which covered eastern Utah. Rivers drained from a tall mountain range on the Utah-Nevada border eastward into the sea, depositing layers of mud and sand over the swamps, which became compressed into coal. Dinosaurs walked in these mudflats and left footprints in the peat moss, which filled in with sand and are now found in the roof of the coal seams.

The layers were later uplifted when the Rocky Mountains rose along with the rest of the Colorado Plateau. The center of the plateau bulged into a giant syncline, the San Rafael Swell. The coal seams became exposed in the edges of the Book Cliffs in a giant crescent, now called the Carbon Crescent that stretches from Green River around to Emery. In the early 1880s the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad was built between Denver and Salt Lake City. My own Great-Great-Grandfather, Joseph S. Black, worked to build the railroad grade with scrapers and horse teams. He discovered a large coal seam that he sold for $3000. It became the Castle Gate Coal Mine, one of the first large mines in the district.

The town of Helper was built to provide extra locomotives to help pull the trains over the top of Soldier Summit. It also became a transport center for the coal coming out of Carbon and Emery Counties. Today, the town’s history of coal and railroads is preserved in the Western Mining and Railroad Museum at 294 South Main St. in Helper. Here’s their website:

The museum takes up the rooms of an old hotel, plus a new annex, and is organized by topic (such as the shadier side of life in Helper, with gambling tables and whiskey stills from Prohibition days) and by community (with rooms for each town in the district, such as Clear Creek or Sunnyside). There was a room on doctors and dentists, with a complete dentist’s chair and equipment, a room on schools, one on laundry facilities, one on sports teams, one for grocery and dry goods stores, etc. Downstairs was a large room with equipment used in the mines, such as rescue breathing apparatus, miner’s helmets, lamps, coal assaying equipment, and diagrams of how coal is mined.

Map of the Carbon Crescent, represented by the red and pink coal deposits around the San Rafael Swell and Book Cliffs in eastern Utah.

A large coal seam is basically a layer that is at least six feet thick and extends left and right of the main portal and into the side of the hill, often for miles. After over 100 years of mining, the coal seams are still extensive and there is enough here in the Carbon Crescent of Utah alone to serve all of the United States for at least 200 years.

One room was dedicated to the Winter Quarters mine disaster of 1900. On May 1, 1900, a new shift had just entered the Winter Quarters Mine Portal 4 when a huge explosion blew out of the portal, sending timbers and coal cars across the canyon as if they had been shot out of a rifle barrel. About 250 men were killed, in some cases wiping out every male member of entire families. At the time, it was the worst mining disaster in U.S. history. This photo is from the Salt Lake Tribune the day after, and was found glued to a board hanging in a school that was torn down many years later. The cause of the accident was eventually ruled to be a dust explosion, and new safety procedures were put into place in coal mines to try to prevent it from happening again.

The coal was slow to get out when miners used the standard hard rock tools of picks, shovels, mules, and dynamite. In the 1950s, automated mining machines were installed, culminating in the long-wall mining machine. The long-wall miner (or continuous miner) is a large shearing blade that slices left and right along a seam, taking three feet of coal in one pass. Behind the blade is a continuous conveyor belt that transfers the coal to the side, then to another belt that transports it out of the mine to the processing center where it is broken, sorted, and shipped off in trains and trucks. Behind the shearer, hydraulic lifts hold the ceiling in place until the machine is advanced. The machine usually is placed at the back of the mine and cuts forward, so the ceiling collapses behind it as it cuts its way out.

It was a much more extensive exhibit that I realized, and I stayed longer than I intended, about three hours. I left at 5:00.

A Little Problem with a Rock

On my way beyond Wellington, some rocks had fallen off of a truck and were scattered across my lane. I didn’t see them in time to dodge, and my right front wheel struck one and immediately began to vibrate. Within a couple of miles my tire was flat. I had to get out the spare (not easy in a mini-van) and change the tire. The rim was dented and the tire itself looked damaged. I drove on the spare about 50 miles to Green River, where I found an open shop. They didn’t have a rim to fit, after several tries and much wasted time. Eventually I had them put the spare tire on the right rear and the right rear on the front and traveled on. It was 9:30 by the time I left.

I had to drive slowly to protect the spare, and it was already dark when I drove down State Road 191 through Moab and beyond to Monticello, where I picked up Highway 491 (formerly 666) through Cortez. I had to pull over in a place called Pleasant Valley in order to take a nap, as it was very late and I was getting drowsy. I finally pulled into the Lightner Creek campground near Durango at about 2:00 in the morning. I was too tired to try to pitch my tent, so I threw a tarp on the ground, laid down a thick comforter and my sleeping bag, and wrapped the tarp over me like a burrito to protect myself from a light drizzle of rain and slept tolerably well.