Earth and Moon today

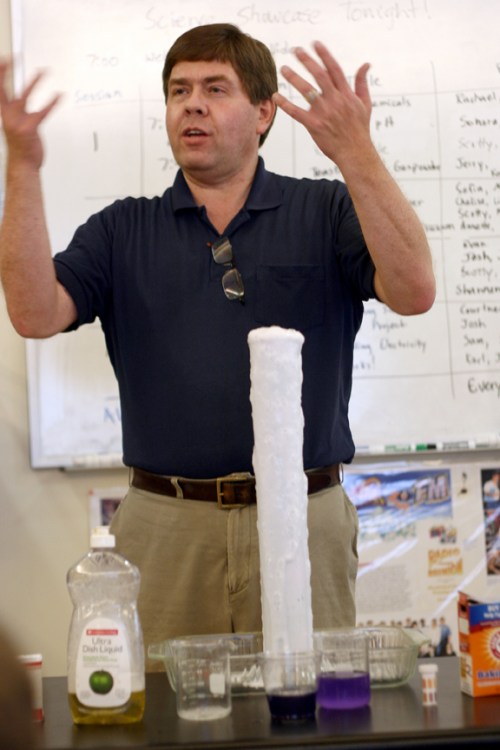

We’re back in session at Walden School of Liberal Arts and this year I’m teaching courses in astrobiology, forensic science, multimedia, 3D animation, and computer literacy. We alternate chemistry every other year, since we are a small school, and therefore I’m able to teach some unusual science classes. Because my focus is on astrobiology this semester, the blog posts for this Elements Unearthed website will have a decidedly planetary science flavor for the next few months. As much as possible, I’ll try to weave the stories of the elements into our quest for life elsewhere in the universe.

I’ve spent much of the summer trying to arrange authentic learning experiences using real data for my students and for the students in the physics classes. I still get e-mails from NASA programs that I’ve participated in, and these often contain some wonderful student opportunities. I’ve been pretty successful finding some fun and meaningful projects.

Our Moon today

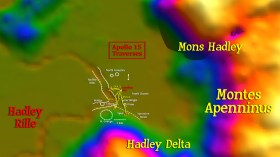

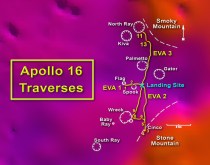

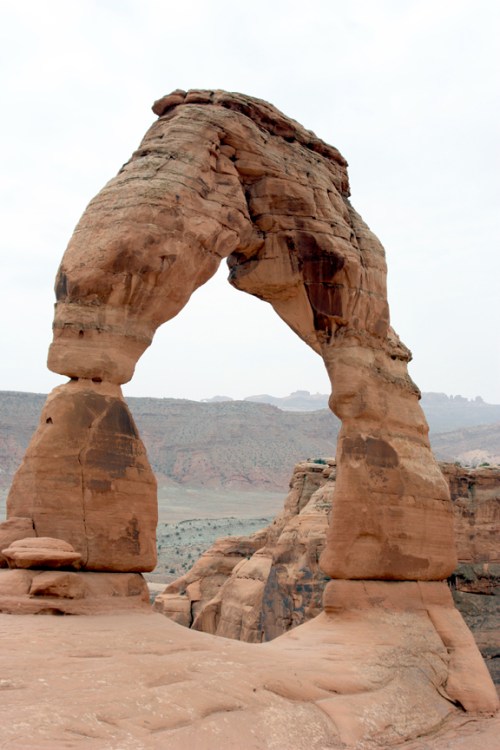

Our first is to create a realistic animation of how the moon formed for the Center for Lunar Origin and Evolution (CLOE) in Boulder, Colorado. Here is a link to their website: CLOE Homepage. They are part of the NASA Lunar Science Institute and study the evidence brought back by the Apollo astronauts, trying to determine how our moon first formed and how it evolved over time. This has important implications for astrobiology because it gives us clues to the early solar system and how planets form in general and how some planets (such as Earth) develop life and others (such as the Moon) don’t.

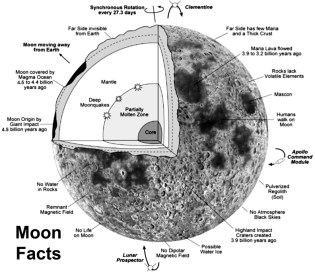

A successful theory of the Moon’s formation has to explain some strange, anomalous facts about the Moon and its rocks. First, the Earth-Moon system has too much angular momentum compared to other planetary-moon systems. No other planet (unless you count Pluto) has a moon so massive compared to the planet, and adding up the total mass and rotational and orbital speeds gives too much energy for a stable system. In fact, the Moon is slowly spiraling away from the Earth.

Second, the rocks brought back show that at one point about 4.5 billion years ago the entire surface of the Moon was molten, a magma ocean, at a time when the Earth already had a solid crust. If the moon formed slowly, by accretion, then there wouldn’t have been enough energy to totally melt the surface. The moon must have formed quite quickly (in a period of only a few years) for there to have been enough heat. Also, since the Moon is smaller than the Earth, one would expect it to have cooled down sooner, not later.

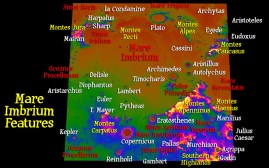

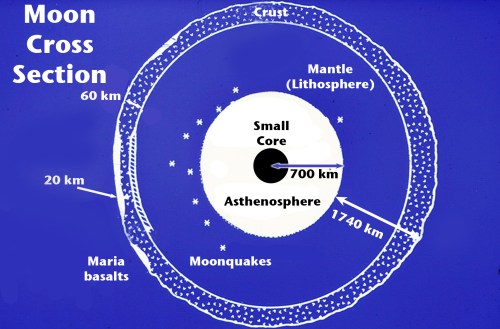

Third, the elemental composition of the Moon’s crust very closely matches Earth, especially Earth’s mantle, right down to the precise isotopes of elements. Fourth, the Moon has a smaller iron core than it should have for an object its size (Earth, for example, has an iron/nickel core that takes up 1/3 of its mass, the Moon’s iron core is less than 5%). If it formed on its own either in Earth obit as a twin planet or was captured later, it should have different isotopes and a larger iron core than it does.

Fifth, the Earth’s axis is tilted about 23.5° from the plane of the solar system (the ecliptic) and the Moon’s orbital path is closer to Earth’s tilt than it is to the ecliptical plane (only about 5° off). Otherwise, we would have lunar and solar eclipses each month.

Sixth, the moon’s elements are different than one would expect for an object that size compared to other similar objects in the solar system. It has more titanium and aluminum but much fewer volatiles – that is, chemicals like water, methane, and ammonia that evaporate easily. Even the rocks are extremely dry, without any hydrates to speak of except small deposits in shadowed craters near the lunar poles. So the Moon is both very similar and somewhat different than the Earth.

How do you account for these facts? The theories of lunar formation prior to Apollo were: 1.) The Moon formed at the same time as the Earth, both accreting from the same cloud of planetesimals, with the Moon already in orbit around the Earth as it formed. 2.) The Earth started out rotating very fast and spun the Moon off. 3.) The Moon formed elsewhere and was captured into Earth’s orbit.

A careful look at each theory shows facts that contradict it. Theory 1 (co-formation) is negated by the high angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system. Theory 2 (spin-off) is contradicted by the magma ocean early in the Moon’s history and by the fact that the Earth couldn’t have ever spun fast enough for this to happen. Theory 3 was the leading contender for years, despite the Moon’s large size, but the identical isotopes show that the Moon must have come from the Earth, not elsewhere. None of these theories can account for the unusually small iron core and lack of volatiles.

Giant impact of a Mars-sized object 4.5 billion years ago

Gradually, during the 1970s and 1980s, a new theory emerged and gained acceptance in planetary science circles. It is called the Giant Impactor theory. If true, then about 50-100 million years after the Earth formed (4.5 billion years ago), a large object about the size of Mars collided with Earth. It wasn’t a head-on collision, more of a glancing blow, and it knocked off a goodly amount of the Earth’s mantle into space and knocked Earth partially on its side while leaving Earth’s core intact. This planetesimal, called Theia, would have formed nearly in the same orbit as Earth and the closing speed was slow – only about 5 km per second. The impactor was demolished after the first collision – most of its iron core spiraled in and joined with Earth, the rest of it joined the splashed mantle material to form a ring around the Earth. The lighter volatile materials escaped from Earth’s gravity entirely. Within a fairly short time (maybe only ten years or so) most of the ring coalesced into the Moon. The heat of this rapid formation caused the Moon’s surface to melt and crystallize. The final lunar surface was therefore a mix of the Earth’s mantle (similar isotopes of oxygen and other elements) and impactor material (different aluminum and titanium). Here is a poster from CLOE that summarizes this theory: Moon formation poster

I find it really fascinating from both a chemical and a planetary science standpoint that by analyzing a few hundred kilograms of moon rocks brought back by the Apollo astronauts, we can tell so much about events 4.5 billion years ago and answer age-old questions. This is why we must eventually send humans to many locations on Mars – even with sample return robotic missions, the chances of answering the riddles of the Red Planet are small unless we have people with trained minds and eyes on the surface to put it all in context and find the right specimens to study back on Earth.

Our job will be to take this theory and turn it into a believable animation. My astrobiology students will research the details and evidence, create the storyboards, and ensure the accuracy of the animation while my 3D modeling students create the actual objects, textures, scenes, and animations. It will be challenging, involving particle effects, physics, and some very sophisticated compositing techniques, but I think we’re up to it. I look forward to the challenge! Meanwhile, I continue to apply to programs that we can participate in where our unique capabilities will be put to good use.

If you’d like a more detailed description of the giant impactor theory, check out this link: http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Dec98/OriginEarthMoon.html

Read Full Post »