It has been some time since I have written a blog post for this site. My work continues at Clark Planetarium, where I don’t get many opportunities these days to pursue the history, mineral sources, origins, properties, uses, extraction, refining, and hazards of the chemical elements. That is, after all, the main purpose of this blog site even if I have occasionally gone on tangents of global citizenship or science education in general. As a result of setting this site aside for several months, viewership has dropped off even if my passion has not.

I continue to work toward my doctorate, with my dissertation proposal going through several drafts this year. I wrote a longer version of the proposal (the first three chapters of the final dissertation, with chapter 3 in future tense) and sent it to my advisor in September. I wanted it to appeal to practicing teachers, but my advisor’s response was that it needed to be re-written in academic language and drastically shortened to less than 15 pages per chapter. Although I resist writing something that only a few Ivory Tower academicians will ever read, I know it must pass the Internal Review Board once it passes my committee, so I have done as he requested. I combined all three chapters together with my appendices, and my advisor has now completed a line-by-line edit. I am working through these suggestions over the next few days as schools shut down for Winter Break and our outreach schedule at the Planetarium eases off.

The core of my dissertation, as it is for any, are the research questions. These are mine:

RQ 1: To what extent can STEM teachers implement student-created digital media projects (SCDM) with three dimensions of choice to enhance student creativity, engagement, and content mastery?

RQ 2: To what extent can informal STEM education institutions develop and successfully implement a science communication contest to extend contact time and improve student motivation and science learning?

As I see it, based on 33 years of classroom teaching experience, there are two problems of practice in STEM education (including chemistry). The first is the problem of student engagement, which I have talked about before on this site. I hope to see how student-created digital media projects can help enhance student engagement and lead to increased creativity, quality, and content mastery. This has been the main thrust of my research all along. As a planetarium educator now, I also see a problem of practice in how to increase our impact as an informal science education institution. We visit 6-8 schools per week (I average about two) and we can only teach one class at a time for about 45 or 60 minutes depending on the lesson, and can only visit a school once every two years (charter schools once every three years). That means we are missing over half of Utah’s sixth graders each year. We visited about 28,000 students this last year, and that is an exemplary task, but how much impact can we really have in so short and infrequent a time?

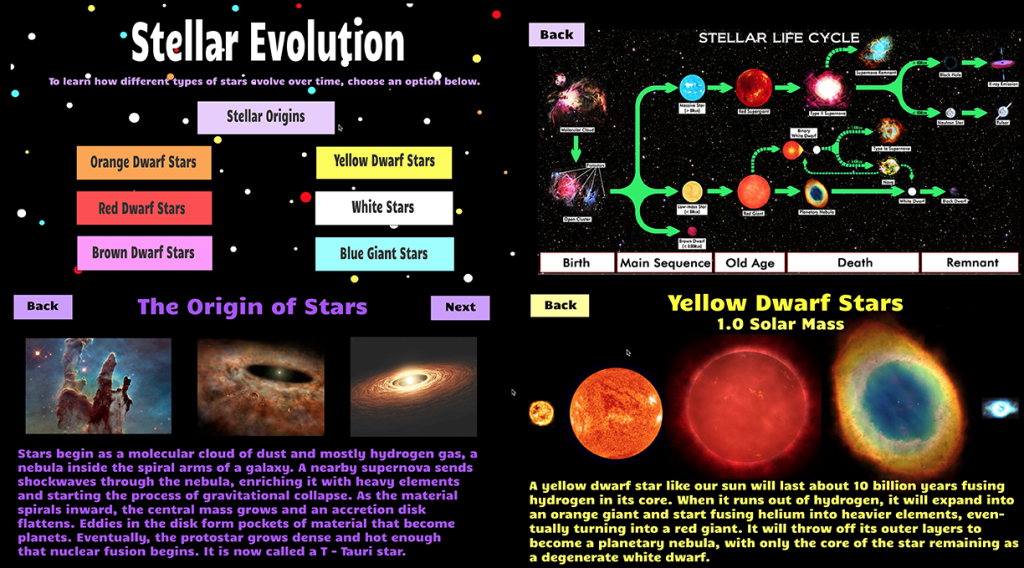

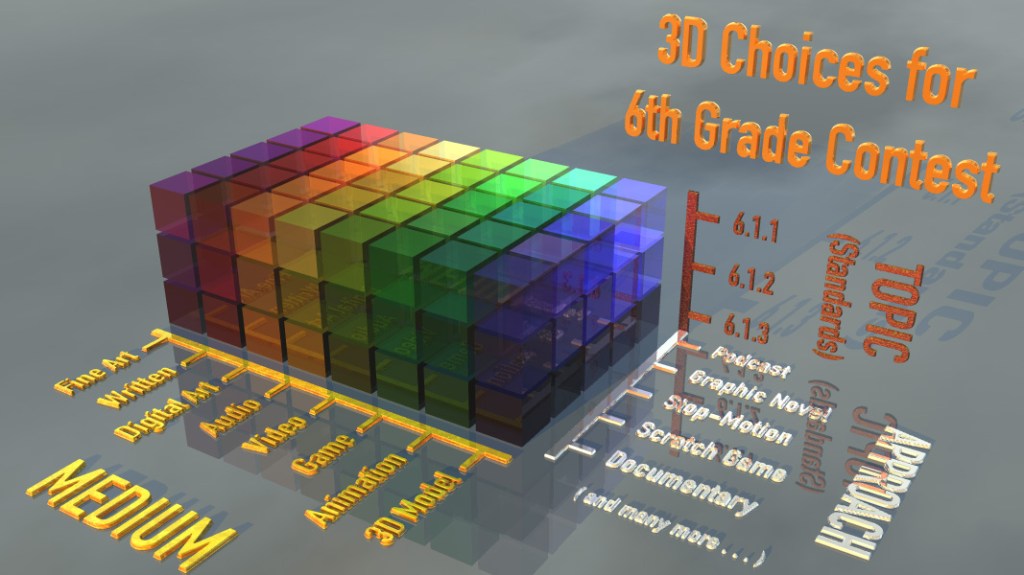

The second question implements the first through a science communication contest we are calling the Cosmic Creator Challenge, where students create their own digital media projects on the sixth-grade space science standards for Utah. You will notice in my first research question that I am using three-dimensional student choice as the experimental variable. I have not yet explained what 3D choice is on this website. Here goes:

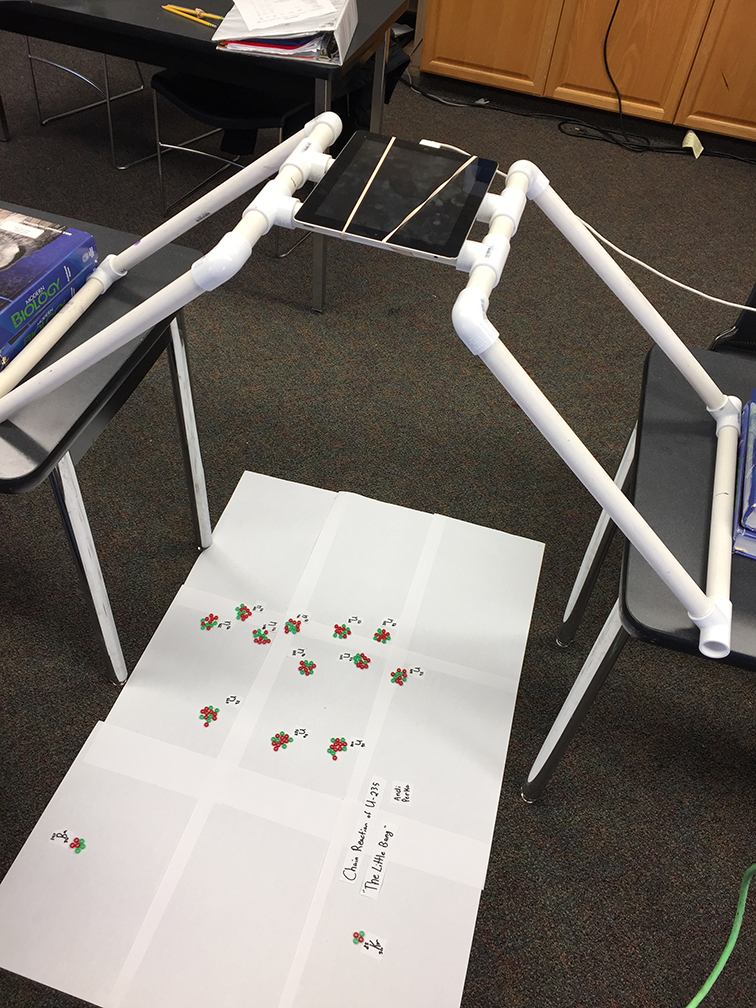

When students are given digital media projects as a way of demonstrating their mastery of chemistry or other STEM concepts, they have three dimension of choice. The first is the choice of topic. Usually, in project-based learning, students are able to choose a specific topic for their projects from a teacher-delineated list or as specified by subject-area standards or objectives. This is the first dimension – choice of topic. The second dimension is usually choice of approach – that is, exactly what format the project will follow. The easiest way to explain this is through the example of a video project: students can choose different video formats, such as a public service announcement (PSA), a news report, a TV commercial, a documentary, or a narrative film (with script, props, and actors). These two dimensions are what are usually given to students for a project-based learning experience.

But with digital media projects, there exists a third dimension. The choice of medium. Usually teachers choose this by having all students create a podcast or a video or a poster or a Scratch game. But what if we allow students to choose their own media type? There are many types of media now; the formats have proliferated and include digital images (pixel or vector-based); posters or infographics; desktop published documents; audio files; video files; presentations or slide shows; animations (several types, including stop motion); websites; games; and various types of augmented or virtual realities.

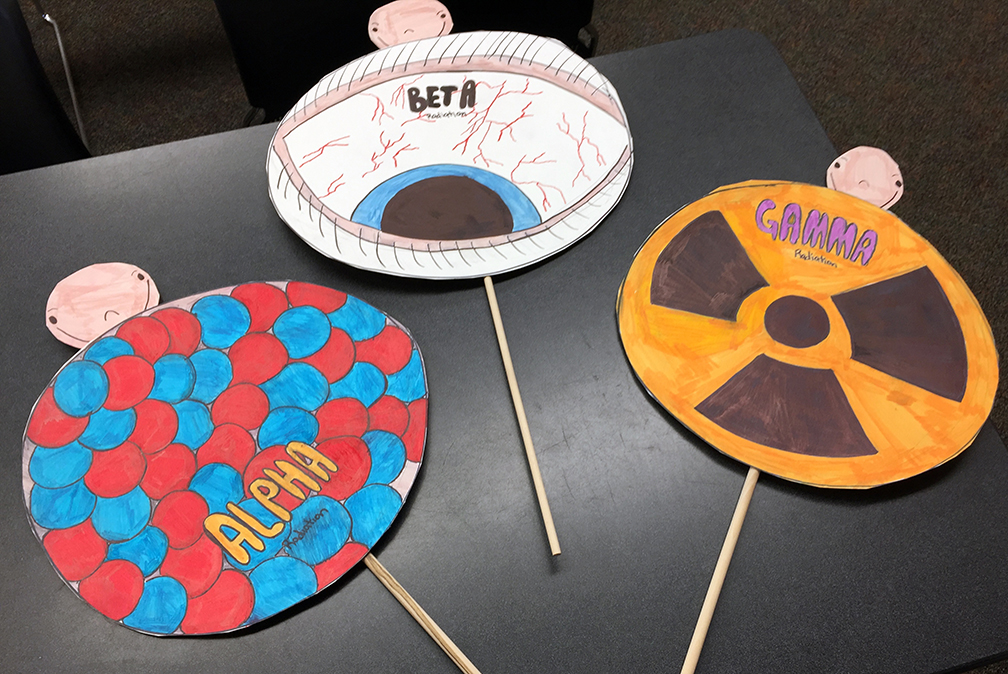

Once you combine all three dimensions, you have a huge number of possible choices for projects that can be based on students’ preferences, experiences, previous knowledge, and desires for learning. The potential for creativity is very high, with students coming up with projects that are unique, effective, fun, and communicate their chosen topic well. Here are just a few ideas for what my students have done in a first-year chemistry class:

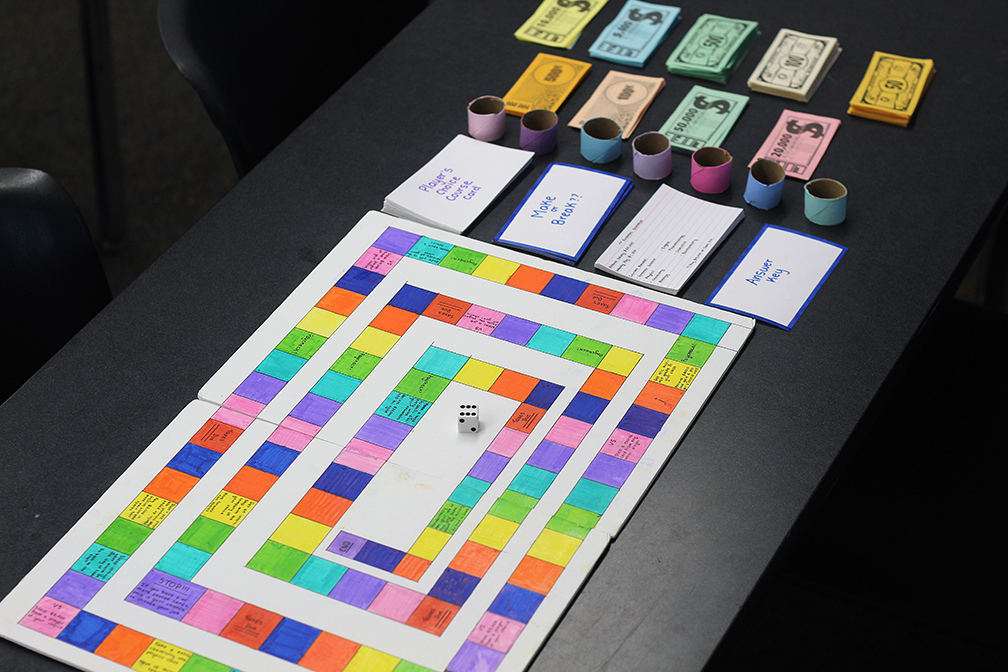

For our first unit on the nature of chemistry, I had a student who chose the topic of careers in chemistry and created a board game that combined aspects of several other games including the Game of Life. Students started the game in college and chose a chemistry specialty, had to pass classes with different life choices popping up, then graduate, find a job in their specialty, and work through to their first promotion while making choices along the way. In the process of playing the game, students learned about careers in chemistry. By creating the game, the student-creator had to research a great deal of information, and did so entirely through her own effort.

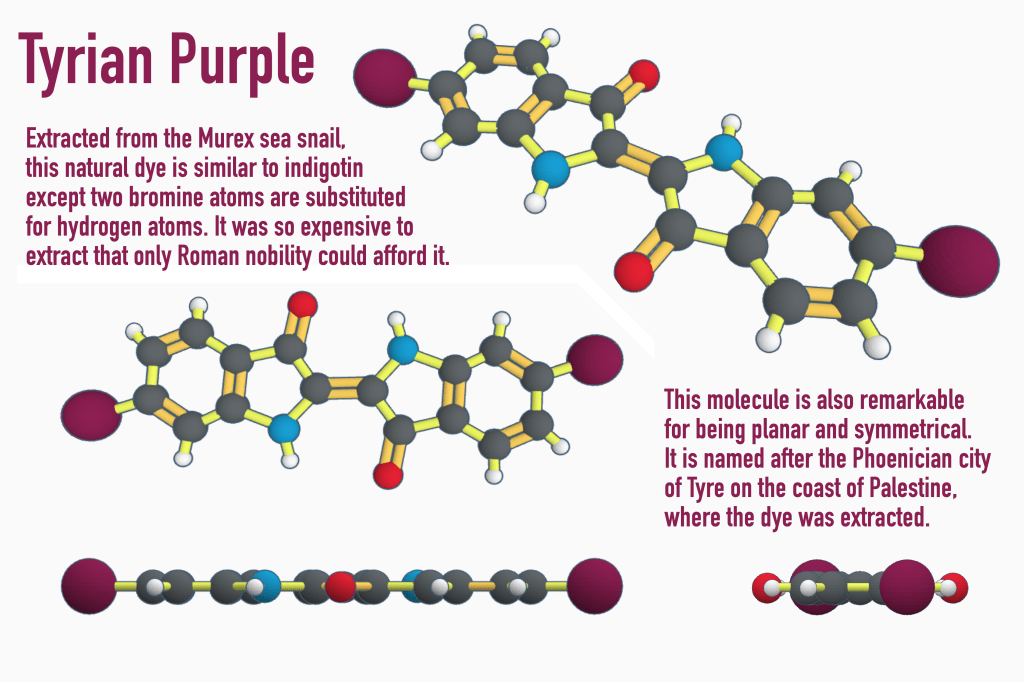

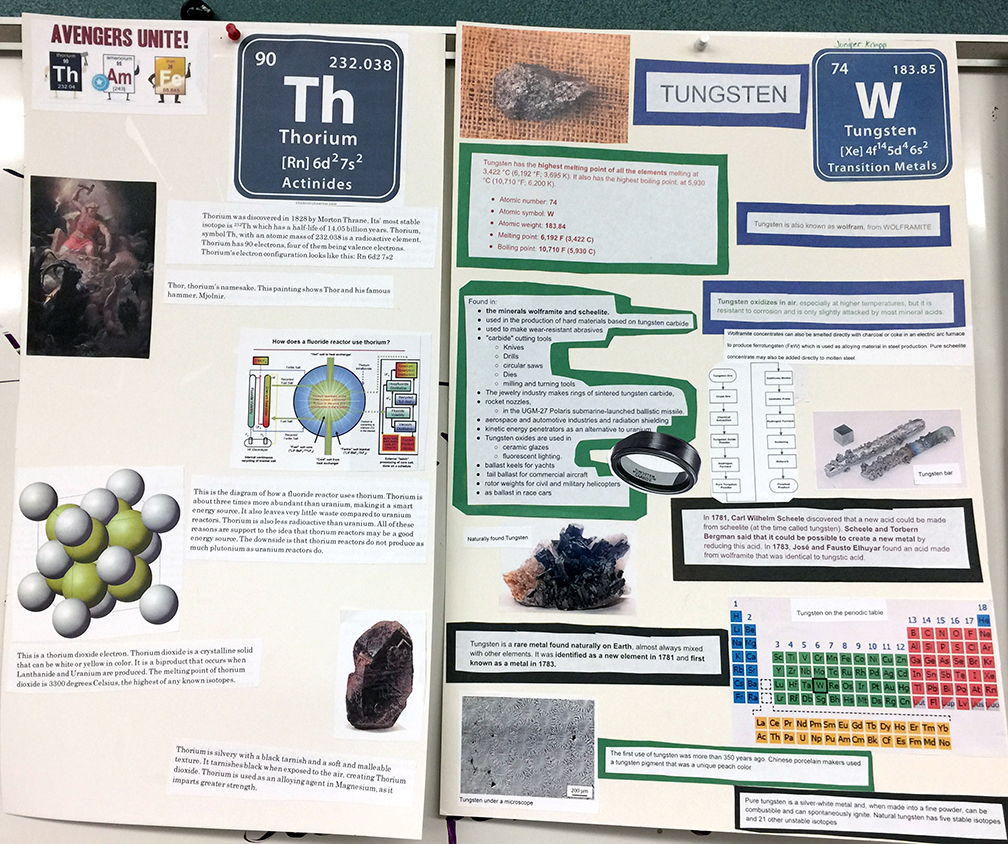

For a unit on the elements, students chose their favorite element (such as Thorium for an Avengers fan) and created a physical poster or infographic on the properties, uses, mining, refining, etc. of the element. They typed up text, inserted images and captions, and created a summary and crossword puzzle game for the back sides. Although the final posters were put together by hand with glue, it could have been laid out in desktop publishing or infographic software for easier editing. Other students were asked to use the poster and summary to play the crossword puzzle as their way of learning from the student-creators.

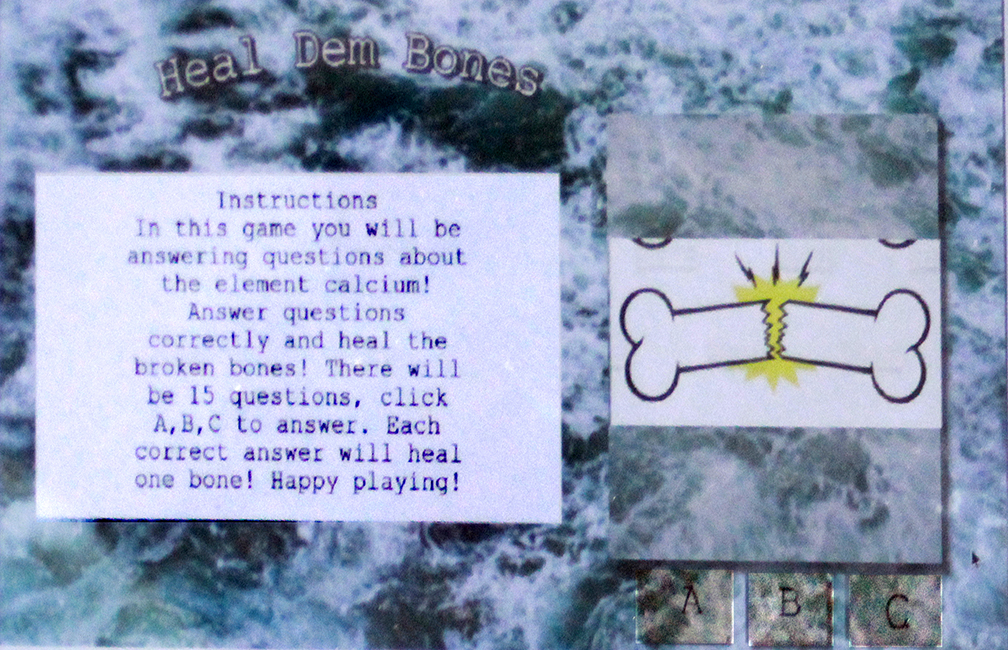

On the same unit on chemical elements, a student choose to create a Scratch game on the element Bismuth called Billy’s Bismuth Bellyache, where answering questions about bismuth correctly led to the gradual building of a bismuth subsalicylate molecule (the active ingredient in Pepto-Bismol). She designed her graphics, stage, costumes, and created all of the coding necessary to play the game. Another student used Scratch to create an interactive word-search puzzle on Strontium or a Heal Dem Bones game for calcium.

A group of students in an A.P. Chemistry class compiled a joke book with cartoons, puns, limericks, poems, and song lyrics related to quantum mechanics. This was based on an offhand comment in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode where data tries to learn about humor by studying a stand-up comedian on the Holodeck. The computer mentions that the funniest comedian ever based their jokes upon quantum mechanics. So I wondered if we could do that. Eventually, this will become a whole animated cartoon hosted by Boson the Clown to a crowd of electrons as they laugh their way to higher orbitals.

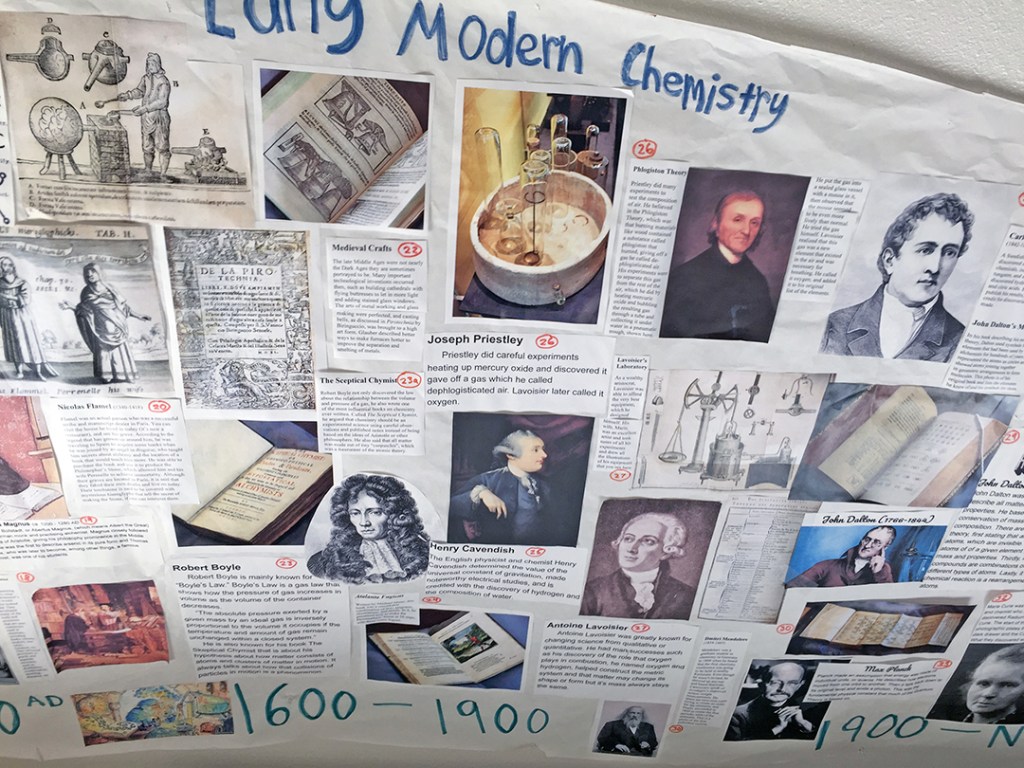

I have had student groups build banners on the history of chemistry, design HyperCard stacks (there is an old one for you) on the elements and their compounds, create videos on elements, create 3D models of molecules and ancient Greek matter theorists, do interviews of experts on the history of chemistry, visited chemical manufacturing plants such as beryllium refineries, cement plants, bronze statuary workshops that use the lost wax technique, chocolate factories, and artificial diamond manufacturers. All of these projects are based on some form of media design. As time goes on, I have done more to encourage student choice of medium and have seen incredible results.

Yet all of these great examples are anecdotal – wonderful stories, but not constituting the type of proof needed by other chemistry teachers and science department chairs to adopt student-created digital media projects (SCDM). This is where my dissertation comes in – I hope to gather statistical evidence that other teachers can effectively adopt these same ideas for SCDM projects and 3D choice in their own classrooms, and that they will see enhanced student creativity, engagement, and learning. Once my proposal is approved, I will establish a science-communication contest at the planetarium for sixth-grade students to demonstrate their understanding of space science concepts (part of the sixth-grade science standards). I will gather data from their projects and student peer assessments to see if creating these projects leads to increased test scores as evidence of learning. By this time next year, this dissertation will be completed and defended and I will be a large part of the way to proving my hypothesis. Then I can return to exploring the elements once again and think of retirement and traveling to more mine sites.

In the meantime, I will report on the elements as much as possible, but my posts will continue to be sparse until then. Bear with me; the end will be worth the wait. I hope the examples shown here will inspire you to try out new ideas and use some student choice of what types of media projects they will create. For any unit, you can specific the topics (or your state standards can) and let students choose their specific topic, medium or software, and their approach. You will be amazed, as I have been.