What I am about to say will be considered as educational blasphemy. I have to say it anyway. Here goes: Education standards do more harm than good.

There, I’ve said it. Now I need to defend my claim logically.

When state boards of education and national committees get together to write new standards, they are doing so with the intention of improving learning outcomes in a subject area such as history or math or science. But I argue that higher standards have not and will not lead to improved student outcomes for several reasons: first, standards become an end unto themselves instead of being a means to the end of improved outcomes. This means-ends inversion leads to a myopic focus on meeting standards, as evaluated by high-stakes tests, above all else and to teachers being pressured to teach to the tests in a misguided effort to increase scores. Even if schools are able to increase scores, it does not mean that students are learning more in any long-term fashion. When school funding is tied to meeting standards, district leaders and principals put emphasis on test scores and encourage teachers to do what is needed to improve them. Shifting time and focus toward passing tests moves students away from inquiry experiments, creative projects, and other activities that make learning fun and meaningful, leading to lower motivation. As classes become boring and meaningless, student learning actually decreases and creativity is stifled. The student outcome that society needs the most is creativity. Education standards therefore hurt society.

Second, standards are meant to be minimal guidelines. Any competent teacher should be able to meet standards and go beyond them to teach with the passion that leads to extraordinary education. Yet teachers who do so and step beyond the bounds of the state standards are often censured and cautioned to stick to the approved curriculum. Teachers are forced to play it safe in order to keep their jobs. Extraordinary education entails risk; playing it safe will never lead to students caring deeply about a subject or learning how to be creative innovators within it.

Third, the very notion of standards is based on the idea of standardization of education, to make all education everywhere the same experience for all students for a particular subject. It is saying that all students are like the Model T Ford, which Henry Ford said one could buy in any color as long as it was black. Our educational system has been based for far too long on an obsolete assembly line model, with students as raw materials entering the factory floor, moving through standard classes taught by standard teachers and emerging as standard models of some outdated ideal of an educated high school graduate, fit only to fill standardized roles in standardized jobs. Businesses complain that they can’t find enough graduates who can think for themselves, develop creative innovations, communicate and collaborate effectively, or even complete basic tasks like reading directions or doing basic math problems that come up. The graduates might have passed a standard Common Core math class and know how to do standard rote problems, but when they face anything in the real world that deviates from the narrowly specific problem sets they are used to, they cannot solve the problem. Since life is one big story problem, they are ill equipped to develop creative solutions to even small challenges.

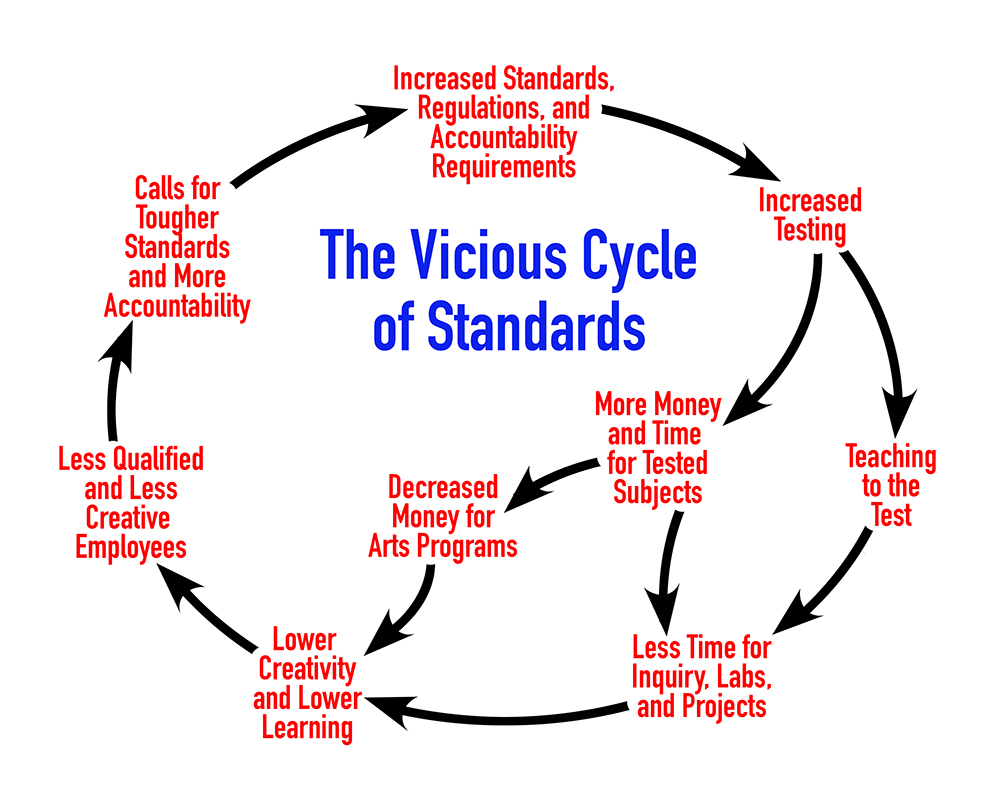

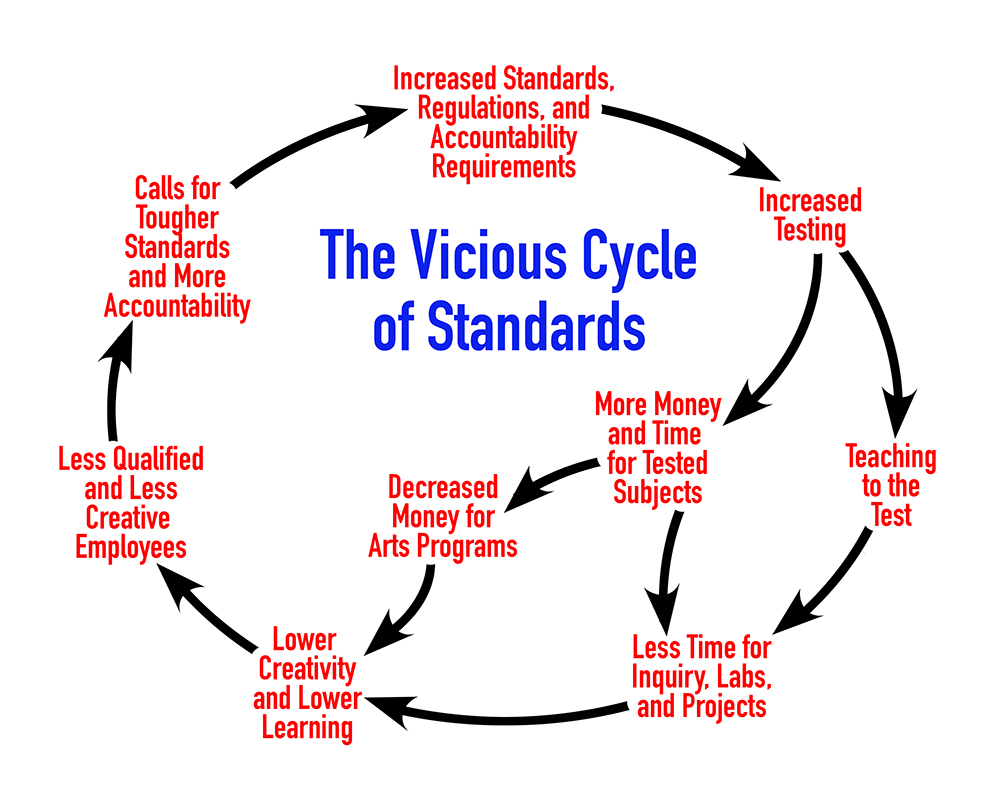

As world problems increase and deepen in complexity, we don’t need standardized graduates. We need graduates who are out-of-the-box thinkers, creative innovators, and problem-solvers who can communicate and collaborate globally. We think that by increasing educational standards we will somehow get the types of graduates we need, but that is simply not happening. No Child Left Behind and its successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act, have attempted to raise national standards with the goal of improving student learning outcomes. They have failed miserably. Students are less equipped for life now than they were 20 years ago before these laws were passed. This is because standards do not, by themselves, raise educational quality. In fact, they can lead to a vicious cycle of diminishing educational quality as shown by the diagram at the top of this post and again here:

Let’s start at the top. National commissions, businesses, and parent groups are successful in their calls for raising national or state educational standards and legislatures have passed laws to hold schools accountable to meet them. In order to hold schools accountable, schools must be assessed and the easiest way to do that is through mandatory testing of all students in critical subjects such as math, science, and English. Those schools that do not measure up are deemed unworthy and labeled as failing schools. Principals at failing schools face getting fired, so they encourage teachers, in many subtle and not so subtle ways, to do what they must to bring up test scores. Facing censure themselves, the teachers start to spend more class time teaching specifically to the test, drilling students and forcing them to memorize enough facts to get through the tests. At the same time, since only certain subjects are being tested, schools tend to put more emphasis on those subjects and provide less time in the daily schedule and less funds toward other, non-tested subjects such as art, music, and humanities. This means that students have less opportunities to learn creative subjects. With teachers now spending more time on drill and practice of testable facts, less time is available for inquiry labs, hands-on activities, and creative projects. Classes lean more toward rote learning and become boring and meaningless to students, who now have even less opportunity to find creative outlets. They do not learn how to collaborate, communicate, solve real problems, experiment, invent, tinker, make, or create. They do not learn how to be innovators, only learning how to regurgitate facts on tests. These graduates struggle in colleges and are not prepared to solve the problems they encounter in real jobs. Employers and business leaders call out for students who are better prepared and ask state boards and legislatures to raise standards. And around and around it goes. It is a vicious cycle.

The worst part of this cycle is the wasted potential I see daily in students who are convinced they are not creative, who prefer to read textbooks and answer questions at the end of the chapters because that’s what they’re used to and know how to do and who never get past the lowest level of factual knowledge in Bloom’s taxonomy because tests rarely get past measuring facts. Even if students learn enough facts to pass the end-of-year tests, they do not retain them for long because the facts have no context or depth, and within a month or two they are forgotten. Yet these students come into schools as kindergartners confident in their creativity. Somewhere along the line, as their attempts at innovation are stamped on repeatedly in the name of standardization, they unlearn how to be creative.

Another tragedy of this vicious cycle is that each step in the process is based on faulty assumptions and non-sequiturs. Having high standards and accountability does not mean we have to design more tests. There are other ways to evaluate schools, and higher test scores do not necessarily mean students are learning more and certainly not better. That we have mandatory tests doesn’t mean we have to cut funding for arts and humanities programs, yet that seems to commonly be the case. This is not an either-or proposition or a zero-sum-game, yet most school districts act as if it were. We can emphasize STEM fields and the arts. We can teach STEM through the arts. I have seen it done effectively. I know of a school near Salt Lake City that teaches science, math, and history through dance. Yes, dance, a program that is usually the first on the chopping block of school districts. The students demonstrated the germ theory of disease through a very effective dance routine. I can give numerous examples of teaching STEM through art from my own classroom, but that will be a future topic.

The worst assumption made by the proponents of standards is that the so-called “soft skills” of creative problem-solving, communication, collaboration, and critical thinking (the Four Cs) are somehow not important for STEM fields and careers. The Next Generation Science Standards actually de-emphasize creativity as a science and engineering practice. Yet all effective scientists or engineers I know of rely frequently upon their creativity and innovation to solve problems that crop up in their research. Creativity is a critical skill, yet our emphasis on standards is crushing it out of future scientists and engineers.

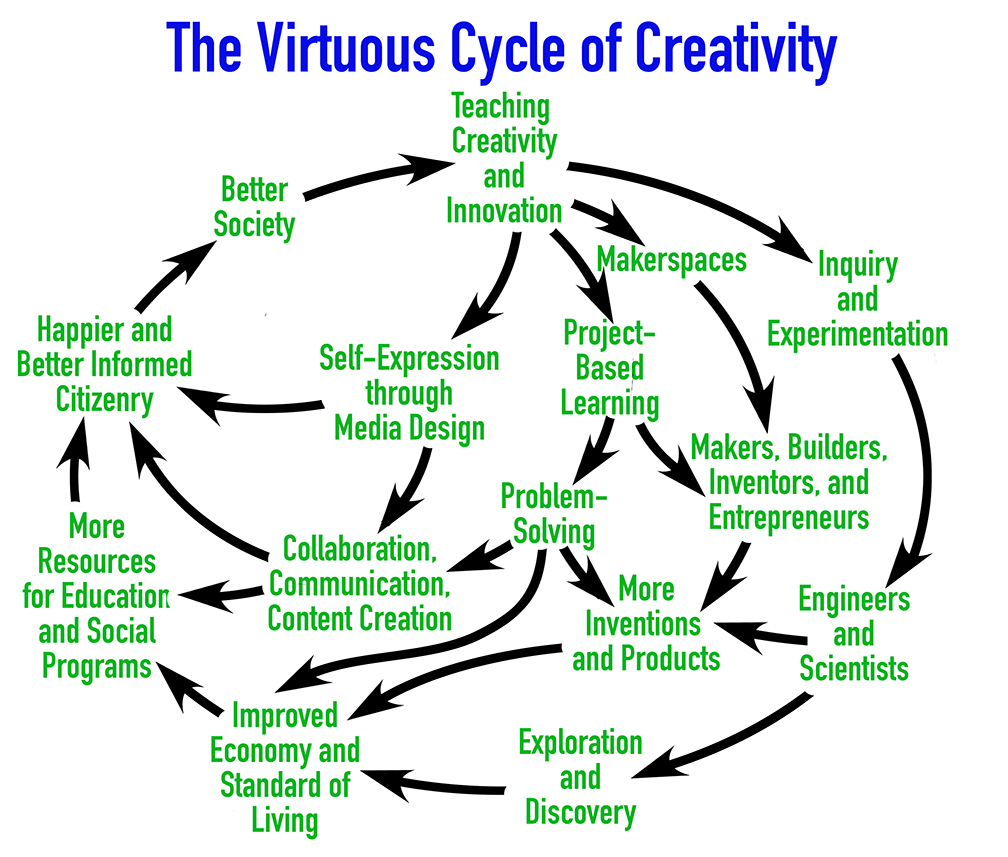

I am in a graduate program titled Innovation and Education Reform but I fear that reform is not enough. What it will take is a wholesale transformation of education, a systemic integration of creativity and innovation into education to meet the needs of the complex problems we face and to stay competitive as a nation. Every attempt we have made at raising standards has merely put more pressure on teachers and students and moved us further away from the model of schools that I have in mind. I would like to see creativity integrated into schools as a virtuous cycle, as shown in the diagram below:

This diagram is more complex but more profound, not because I am claiming any level of profundity, but because the ideas expressed here are rarely examined in this combination. Starting again at the top of the diagram, if we deliberately teach students to be more creative and innovative (how to do this will be the subject of my dissertation) then there are several avenues that should be pursued. The first is that science classes should teach the processes of inquiry and experimentation, or what we used to call the scientific method. Reducing science to a body of facts is to render it dry and meaningless when scientific discovery should be an invigorating and exciting process followed by all students. We cannot expect future scientists to make new discoveries if they do not learn the process of inquiry.

I believe that all schools should have well-supplied and supported makerspaces where students can learn to tinker, make, build, and invent (please refer to my previous blog post for more on this). Part of the makerspace’s purpose should be to teach entrepreneurship and the process of invention, the engineering design cycle, and manufacturing and marketing skills. For a good example of this, look at the Innovation Design program developed by International Baccalaureate. I had the opportunity to be trained and teach this program and it is rare even for IB schools to offer it; mine was one of only a few such programs in Utah at the time.

Teaching creativity should also involve project or problem-based learning (PBL), with a focus on solving problems through design and developing skills for team work, collaboration, and communication. Teaching creativity and innovation through inquiry, making, and PBL will lead to increased scientific exploration and discovery, to more inventions and better products, and to starting up new businesses that will improve our economy and standard of living.

Another area of teaching creativity and innovation that I believe does not get enough attention (and is worth a research project or two this semester) is to teach students how to express themselves through media design software and design thinking skills. Even if teaching these skills only leads to critical media literacy it will be worth the expense in computers and software, but if done right it can enhance students’ creativity through allowing them more avenues to express themselves, to find their voices, to communicate their ideas, and to design educational content that will teach others. I think that we have not done enough research on the importance of training students to be teachers. I follow the old saying (with my own modification): “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man how to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime. Train him how to teach others how to fish, and you feed a village forever.”

With more inventions and products, more educational content, and a higher standard of living we will have more resources available to improve education and other social programs. This will lead to happier citizens. As we teach others how to evaluate media claims and how to express themselves, we will build better informed citizens and allow voices to be heard who have been marginalized before. We have only to look at the misinformation out there concerning the effectiveness of wearing masks during this pandemic to see why scientific and media literacy are critically important social skills. Better informed citizens contributing their own voices will make better decisions both as consumers and as voters, which will lead to a stronger democracy and a better, more equitable society. This entire process will feed back on itself as a virtuous cycle; teaching creativity will lead to more creativity which will lead to a better society and increasing recognition of the importance of teaching creativity and innovation.

Given the complex challenges our society faces, we need to completely overhaul our educational system. I see this as the only way to fully integrate creativity and innovation, which must be done to solve our problems and keep our nation competitive. Now, hopefully, you see the rationale for why I am getting my doctorate and why my dissertation will be about how and why to teach creativity. I can see no other area where I can contribute more.