David Black with Neil Armstrong’s space suit, July 20, 2019.

As I write this blog post, I am in Washington, D.C. attending a Teacher Innovator Institute sponsored by the National Air and Space Museum (NASM). It is July 21, 2019 and I’m a bit exhausted after helping out as part of the NASM Crew for last night’s celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing.

It was quite the party, and NASM has been in the middle of all the planning and organization as the sponsoring institution. They have tents set up along the National Mall in front of the museum with booths by aerospace companies and NASA explaining why we went to the Moon and why we need to return. There are hands-on activities, models, virtual reality tours, simulators, and experts on hand to explain everything and the crowds are thick. On Friday night we were invited to the VIP area to view the Go For The Moon multimedia presentation, which they projected onto the Washington Monument and large screens on either side. They have been setting up large speaker systems around the Mall all week, and the presentation did not disappoint. It was fantastic, and you could really feel the rumble as the Saturn V rocket blasted off as if the Washington Monument itself were being launched into space. It was like being there.

The Air and Space Museum celebrating the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11.

Then, from 8:00 pm until 2:00 am NASM hosted a celebration for tens of thousands of people. As part of the small army of volunteers helping out, my job was to judge some question responses for a series of scavenger hunts throughout the museum on the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs. There were hundreds of teams racing throughout the museum looking for answers to questions that involved artifacts of the space race and the moon landing. Contestants sent in text responses, photos, and short videos of themselves completing challenges. We awarded bonus points or took points away from the automated scoring system. Other volunteers managed the lines to view Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit, count visitors, and be on hand to answer questions.

The Capitol Building during the 50th anniversary celebration of the Apollo 11 landing.

It was an amazingly well coordinated production that has been in planning for over a year. They had to get a Joint Resolution of Congress to be able to project onto the Washington Monument, which took time. They had live bands, showings of the HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon, and even a viewing of 2001: A Space Odyssey. The Mall was packed with people watching the multimedia show, and all of this in the most brutal heat and humidity I’ve ever experienced in Washington, D.C. I am proud to have been a small part of this celebration.

Rover rolling over human subjects on the National Mall during the Apollo 11 celebration.

The Teacher Innovator Institute is in its second year and each year 30 STEM educators are selected for a two-week program at NASM. We have been out at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center near Dulles International Airport and at museums along the Mall. The Hazy Center is an annex of the main museum on the Mall, and houses the Space Shuttle Discovery and an SR-71 Blackbird, among many other historic aircraft. They also have a large curatorial area for restoring donated aircraft, such as the Flak Bait bomber currently being restored. We got to hear a panel discussion with two World War II airmen, including Colonel McGee of the Tuskegee Airmen. We’ve heard presentations from last year’s cohort and practiced STEM education activities, such as building a giant geodesic dome out of PVC behind the space shuttle.

A LEGO spacesuit (complete with Buzz’s reflection and a Moon Maid).

The purpose of the Institute is to take teachers who are already innovators and train them in best practices for STEM education through informal education experiences. By informal, we mean educational programs that are not part of the public K-16 education system, such as museums and educational foundations. I’ve been fortunate to work with planetarium directors, museum educators, and NASA Education and Public Outreach personnel on many occasions and this is a great opportunity to finally learn more of how they approach education through objects.

A giant map of the moon

Museums are largely about objects, or artifacts. It could be a life-sized model of a giant shark hanging up in the Natural History Museum, the Hope Diamond, Lunar Module 2 in the Air and Space Museum, or Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit. These objects are valuable partly because of their intrinsic value (such as the rare blue color of the Hope Diamond) but mostly because of their provenance, or the human lives and events that these objects have touched. What makes Neil Armstrong’s suit more intrinsically valuable than Jim Irwin’s suit, which is in a case at the Udvar-Hazy Center? Neil’s suit had thousands of visitors last night, whereas Jim’s suit is largely unvisited. Both are made of the same materials and have been carefully preserved and displayed. Personally, I am more in awe of the Apollo 15 suits than the Apollo 11 suits, because their owners stayed longer on the Moon, did more science, and made more fundamental discoveries including the Genesis Rock, a piece of lunar anorthosite that Dave Scott and Jim Irwin brought back and which determined the age of the Moon. But Neil’s suit was the first on the Moon, and that gives it a greater significance to most people.

Jim Irwin’s space suit from Apollo 15

Teaching in informal settings such as a museum is very different. Here, educators do not have a captive audience. People wander around, and some just wander through whereas others will stop and engage with an exhibit. If we want learning to occur, then engagement is crucial, as I have discussed in a previous post. What are the factors that encourage people to linger longer? How should the exhibits be displayed, and what holds people’s interest? How do you draw people in, get them hooked, and activate their curiosity? These are critical questions in informal education.

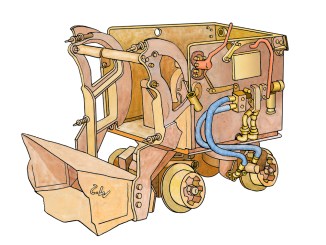

Mars 2020 rover’s sample collection device, with a model of the rover.

The Air and Space Museum was first opened in the mid 1970s and has not had a major complete overhaul since. Individual areas have been upgraded, but some have not and it shows. One of our tasks has been to visit exhibits and evaluate their effectiveness for engaging middle school students. I helped review the Space Race gallery, where the displays are static with no interactivity and no multimedia unless you count the single video screen playing an eight-minute long movie of talking heads that you couldn’t see because it was angled to perfectly catch the glare of the sun through the afternoon windows. Oh, there was one standalone pylon with instructions for going online to listen to John Grunsfeld describe what it was like to repair the Hubble Telescope (an obvious recent addition), but no one was doing it. The gallery had no flow to it, no sense of a hierarchy of events, no relevance to the students’ lives. A middle school student might walk in because of the Hubble Telescope display, but they will wander out again in under three minutes. The best things here – Dave Scott’s spacesuit, for example – are tucked away into almost hidden corners.

Painting Apollo in a tent on the National Mall

The limestone facing of the museum was supposed to be four inches thick when the museum was constructed, but budget cuts reduced that thickness to only one inch and they are beginning to buckle and crack. They must be replaced, so while construction is going on, the museum is re-inventing itself inside as well. So I am thinking of how Air and Space might change to better engage students and the general public.

Lunar Module 2, on display in the National Air and Space Museum. This was the LM that was supposed to be first to test in space, but problems with its construction led to slipping the test to LM 3, which became the Apollo 9 mission.

We have received training on how to introduce and extend the learning that artifacts can provide. We have had the chance to examine some rare artifacts indeed, some of which the Smithsonian preserves but do not display because of their priceless scientific value. On Thursday we went to the Natural History Museum and were asked to find an object that represented us. I found some trilobite fossils that were collected in the House Range of western Millard County, Utah. I grew up in that area and my grandfather had a mining claim for collecting trilobites near where these specimens were collected, in the Wheeler Shale formation. He would take me out to his claim when I was a boy and we would dig into the dark gray shale beds and split them open with a chisel and hammer. We had buckets of them. So they represented me through memories of my grandfather whereas they would just be interesting fossils to someone else. The trilobites have a personal connection. Visitors to museums must make personal connections to the artifacts in order to engage with them.

David Black holding a piece of Mars. This meteorite was found in Antarctica and was identified by the oxygen isotopes found in small bubbles inside it as matching those on Mars. There is an extra hand helping me (thanks, Marc) because I don’t want to drop it. Like I would do a thing like that . . .

I had been through the meteorite, mineral, and gem galleries there several times in my life, so when they took us back past the meteorites and the moon rock displays, I was wondering if there was anything new for me to learn. Then they opened an almost hidden side door and took us through a security corridor to the meteorite vault, where meteorites from all over the world are kept. Our expert guide, Dr. Cari Corrigan, explained her trips to Antarctica to collect meteorites, and brought out some truly historic finds – valuable because of their rarity and their histories. We got to hold (wearing gloves, of course) pieces of the Allende meteorite, which fell in Mexico in 1969; the Peekskill meteorite, which famously dented a car; the only meteorite to injure a person (it went through a ceiling in Alabama and smacked a lady named Ann Hodges on the hip); and the Chelyabinsk meteorite that exploded over Russia in 2013.

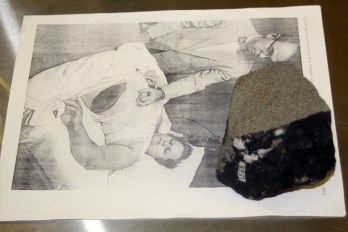

Ann Hodges of Alabama and a piece of the meteorite that hit her and caused the bruise in this photo.

Then Dr. Corrigan pulled out some other meteorites and let us pass them around and take photos. A lunar meteorite, blasted off the Moon. A martian meteorite (we know it is from Mars because of the oxygen isotope ratio in the small pockets of air trapped in the meteorite). These are valuable because of their rarity and scientific value. And they’re from other planets!

David Black holding a piece of the Allende meteorite that fell in Mexico in 1969. This meteorite is the oldest object on Earth at 4.65 billion years old. The white fluffy patches are probably solar system dust bunnies, and there are even pre-solar grains in this rock that are older, perhaps 5 billion years old.

And then, as I was holding the lunar meteorite, it slipped out of my gloved hand and dropped to the floor. Yes, I dropped the Moon. It was unharmed, fortunately, and Dr. Corrigan didn’t see me drop it. Thinking about my klutziness afterward, I realized that this rock was blasted off the surface of the moon, the heat of the impacting object melting and fusing it. It traveled through the vacuum of space for 250,000 miles, then came screaming through Earth’s atmosphere at supersonic speeds, heating to incandescence until it slammed into the ice of Antarctica. Then glacial forces ground it up into the margin of a mountain range where a scientist found it. I don’t think a three-foot drop to the floor is going to do much to it. I would not, however, recommend this as a way to have students engage with a meteorite.

The Hope Diamond in the National Museum of Natural History.

We are learning all the time how to be more effective at informal education; how to engage those middle school students. Take the Hope Diamond. I first saw it in 1982 when I was fulfilling a Congressional Internship here in Washington, D.C. It was rather randomly stuck in a static display case without much signage or anything else in a small gallery of gemstones. The glass on the case was smudgy with fingerprints and it was surrounded by people, so I didn’t get much of a chance to see it. Now, it is in its own space in a rotating stand so that people can see it from all sides for a much better view. But the glass was still smudgy and there were still lines of people when I saw it in the afternoon. On Thursday, we were there at the opening of the museum and few people were around and the glass had been cleaned. There are some signs on the wall, but no interactivity. The gem and mineral collection was redesigned over ten years ago and so there isn’t much interactivity or multimedia throughout. The display is still not very engaging, although improved.

A group of Teacher Innovators in the meteorite room at the Natural History Museum. Dr. Cari Corrigan is fourth from the right on the back row.

What can be done to improve it still? A good example is the International Spy Museum, which has recently been rebuilt near the L’Enfant Plaza south of the Mall. You are given the name of a real spy encoded on a magnetic card. You start at the top learning about some real spies throughout history, such as Mata Hari, with video pylons and screens playing short videos, with interactive stations that read your card and allow you to progress in your mission to be outfitted with devices, given a disguise, breaking the codes, traveling incognito, etc., with real examples of each aspect on display along the way. The museum is built to flow you through the process in one direction, winding around through but with plenty of choices for things to do and see. After two hours, which was all the time we had to be ahead of the general public (we got in there early), I had only made it through half of the museum. My card is good for a month; if I have time tomorrow, I will return. It is that good.

A balloon replica of Neil Armstrong’s boot about to be planted on the moon. Or at least in the Air and Space Museum.

The objects in the museum have not changed. Their intrinsic value has not changed. What has changed is the human dimension – the personalization of the experience and making it relevant, the stories behind the objects and how the visitors fit into those stories. At the end of your mission, you find out if your spy was successful at their mission or not and if you made the right choices. You become the spy and immerse yourself in the experience.

How could we do this with the Hope Diamond, or Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit? With the personal history behind these objects, you could take the role of one of the owners of the Hope Diamond and find if the “curse” claims you or not. Or you could become a gem yourself – you must be dug up in the Golconda diamond fields or the Cempaka diamond mine in Borneo (which isn’t even mentioned in the Smithsonian), be smuggled out of the Mogul’s collection, sold to traders, cut and polished, sold and traded, set in a necklace, worn by a ill-fated rich daughter from a famous family, etc. You could become an astronaut and go through training and fitting and a mission and find if you make it back alive. Along the way, you’ll learn the history and the science because you are invested and engaged. It is personal. It has the human dimension that too many museums fail to capture.

Some of the NASM Crew, a group of volunteers and science teachers who helped with the 50th anniversary Apollo celebration at the Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Last night, tens of thousands of people engaged with space science and history. They had fun and it was crazy but there was so much learning going on. I saw the GooseChase participants learning as their responses came in. They were actively, creatively engaged.

Engagement, innovation, and creativity must come first in any educational setting be it formal or informal, a museum or a classroom. Then learning will follow.

The Apollo-Soyuz display in the Space Race Gallery at the Air and Space Museum. When we arrived to begin our volunteer efforts, the museum was closed (it was cool to walk right in through the staff entrance with our badges). There was no one there. Then, when the doors opened at 8:00, there were large crowds of people wanting to engage in space science education.