A painting I did of the old homesteader’s cabin at our ranch in Tooele County. It was built at the lower spring by the lowest of three irrigation ponds. My grandfather remodeled an old post office building that he had hauled out to the ranch from the Dugway Prooving Grounds which was placed at the highest pond near the upper spring.

As I began my doctoral program in Innovation and Education Reform at the University of Northern Colorado in the fall of 2019, I knew that this would be a challenge, especially at my age. I did not want to waste any time getting through this program, which meant keeping a sharp focus on my reasons for getting this degree. I knew that to move forward toward an EdD now could only be done if I had a passion for understanding the questions I have uncovered as a science and technology teacher over 30 years, questions that can only be answered through sustained and deep research.

I know that I am not doing this for the money. With only ten years or less left of my teaching career, I will never make up the cost of this program in higher salaries. I am not doing it to change jobs (although higher pay would be nice) or because I’m bored with what I am doing. I like teaching high school science; that’s why I’ve done it for 30 years. Getting this degree has to be because I have compelling questions that can be answered in no other way; this is a passion project.

Before even applying to various graduate school programs, I sat down and identified six areas that I wanted to learn more about and where I could contribute my own experiences. I’ve mentioned them before, but here is a quick summary:

1. The nature of creativity and innovation: their importance to society and students, and how to teach them.

2. Project and problem-based learning: Gold standard PBL, how to implement it in a classroom and across entire schools, how to engage students in the process, and how to achieve quality results.

3. Using authentic data in science classrooms: What are the tools, theory, and pedagogy for using big data and conducting field studies?

4. Global awareness: why this is important and how to teach it through global problem-solving projects and best practices for collaborating with other students globally.

5. Students as teachers: Teaching media design skills to students so that they create educational content and become teachers. What is the theory, evidence, and pedagogy for this? This is one area of a greater concept of students as innovators.

6. Gamification of education: How can games, both traditional and digital, help to enhance student engagement, learning, and retention?

Official patent illustration of my grandfather’s headgate design. Instead of a canvas dam with dirt thrown on it, which leaked terribly and wasted water, this headgate did not leak because of the folded sheet metal sleeves that it slides up and down in. He built the prototype in the ditch behind our house, and my dad convinced him to add some angle iron across the top and holes in the upright bar so that a crowbar could be used to raise and lower smaller versions instead of a screw and wheel.

Of these six topics, the central one which ties all the others together is the first topic: the nature of creativity and innovation and how to teach them to students. My education and teaching career keeps coming back to this topic ever since I took a course in Creativity as an undergraduate at Brigham Young University in the fall of 1981. Even before that, I grew up living next door to my paternal grandfather, A. T. Black, who had a workshop behind our two houses and taught me how to use various tools to build things. He was always working on some project or other and never met a Popular Science or Popular Mechanics magazine that didn’t give him more ideas. He was only able to achieve an 8th grade education but kept learning all of his life, and I wonder what he could have done with an engineering degree. He invented a new type of headgate for controlling irrigation water, had it patented, and hired a sheet metal company in Salt Lake City build it for him, then marketed it to the various irrigation companies in our farming region. Most of those headgates are still in operation. He built and ran the first telephone system in our town, and built five rotating Christmas tree stands which still allowed the trees to have electric lights. These were used for our town’s annual decoration. Our ranch house in Tooele County was over 20 miles from the nearest town, yet we had electric lights from an alternator hooked to a waterwheel; a solar powered water heater; a butane stove, lights, and refrigerator; and even telephone service for a time with the nearest neighbor over seven miles away long before cell phones or even CB radios were a thing. We were off the grid long before anyone had ever heard of it.

I do not have my grandfather’s knack for building; I cannot cut a straight line through a board with a handsaw to save my life (much to his chagrin). But I hope to have inherited his creativity in other ways. It has always fascinated me how one person, without much education, could be so creative while many of my students don’t believe that they are creative at all. Is creativity something that a person is born with, an innate talent that should be encouraged? Or is it a cognitive skill that anyone can develop? Is it a process with definable steps, or is it a matter of ideation or insight, of recognizing an inner daimon or genius that sends an “Aha!” moment to consciousness after long incubation on a problem? Can this state of insight be extended into a continuous flow of creativity? Can it even be taught? These issues fascinate me and will ultimately drive my doctoral program and eventual dissertation research.

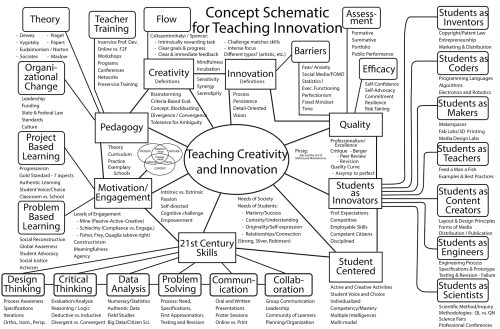

I decided that this topic, the natures of creativity and innovation and how to teach them, would be the first step toward all of my possible dissertation topics. I choose it as the subject for my fall 2019 EDF 670 class, where we were required to build a Literature Review. But before I could do any useful research, I knew that a better analysis of creativity and innovation as concepts was necessary. I took several days to work out a schematic concept diagram or web of ideas surrounding how to teach creativity and innovation. I have continuously refined and expanded this diagram as more research has come my way. I am progressively working my way around it, digging more deeply into each sub-topic. I suspect it will take the rest of my career in education to thoroughly explore it.

Here it is. I have kept the resolution fairly high and the file dimensions large so that it will remain readable.

Concept web for teaching creativity and innovation, created to help define related concepts in preparation for my literature review class. I have revised it several times since then.

Let’s take a look at the central concepts. In future posts, I will explore each one in more detail. In the next post, I will share my conclusions about definitions of creativity and the literature review that came out of this research. For now, however, let’s conduct an overview of the diagram.

The central hub of this web is Teaching Creativity and Innovation, which must remain the focus since I am studying education, after all. Teaching creativity to students has benefits for society. We live in an innovation economy, yet we do not systematically teach students how to be more creative or innovative. We just somehow expect they will pick it up somewhere. Beyond the good it will do to society, creativity is a skill that will benefit any student by leading them toward greater mastery of concepts, developing originality and self-expression skills, enhancing their curiosity, and ultimately leading to lifelong learning and success. As a means of developing better mastery and competency, I experimented with a different grading system focusing on mastery and creativity in my biology classes this last year, and I will report on these efforts in later posts. Many good things have come from this, and I am revising the program for this fall.

The inner ring of sub-topics establishes the major concepts to consider in teaching creativity and innovation. First, how can we define these terms? Are they actually the same thing, or is creativity merely a subset of the characteristics or process steps required for innovation? As suggested above, there are several competing definitions of creativity. They are: (1) Creativity as innate personality trait; (2) Creativity as a set of cognitive skills which can be practiced; (3) Creativity as insight and ideation, or the development of new and unique ideas; (4) Creativity as a state of creative flow at the intersection between high challenge and high skill; and (5) Creativity as a problem-solving process. More will be said about these in my next post.

Averno Thompson Black, my paternal grandfather, one of the most creative people I have known.

Innovation, on the other hand, seems to denote a process (often called problem-solving, engineering design, or design thinking) that includes creativity as divergent ideation and insight but also requires convergent thinking and evaluation of the worth of ideas, along with building and testing a prototype, revision, and final distribution of the solution. It is an iterative process that takes resilience and a tolerance of failure, since testing a prototype until it fails is a common part of the process. I have not yet fully explored this area, but my experience teaching innovation design classes leads me to this conclusion.

Assessing the quality of solutions is a necessary part of creativity and innovation. I have been exploring this part of the diagram over this summer (2020) and there isn’t much out there. Ron Berger, now with Expeditionary Learning, has developed a process of peer review of student work that he calls Critique that has led to good results at High Tech High and other schools, and which I implemented into my astrobiology class this summer as an experiment. It worked fairly well, but I need a more thorough and careful implementation this coming fall. I will report on these experiments in a later post, but you can see more of our project work at my other blog site: http://spacedoutclassroom.com.

I have also developed some materials for teaching quality, such as a diagram illustrating what I call the quality curve: Effort and quality are not linear in relationship. They are exponential. To double the level of quality in a project does not take twice the effort but four times as much effort or more; it takes 80% of the final effort to raise the quality of a project from good to excellent or professional. I deal with students who have high anxiety and many are perfectionists; they will not turn in assignments until they are perfect, which they can never be, because the effort vs. quality curve is assymptotic to perfection. I don’t know how this could be studied in the classroom, but it would be very informative to see how well this holds in real life. The key then is how to get students to recognize and put in the effort to reach excellence or professionalism without holding out for perfection. This takes a degree of self-efficacy that many of my students are lacking. Assessing quality and innovation is an entire large topic of its own.

Another painting I did of the old ranch house for a watercolor class in college. I can’t cut a board straight, but I do enjoy fine and digital art. My creativity comes out in different ways than my grandfather, but I learned how to be creative from him.

At the same time, there are barriers to achieving creativity, innovation, and quality. These include anxiety, as mentioned above, having poor executive functioning skills (which is true for many of my students), or having a fixed mindset where failure is not tolerated and revisions are not considered. Students need the time to recognize where they need to improve and then make revisions until they achieve quality. Teaching this is one key to achieving innovation in students, and an area I am just beginning to study. Not much seems to have been done in this area yet, but it may be that all my searches keep bringing up teacher quality, not students achieving quality and how to teach it. I need to refine my searches and dig deeper. This is where the diagram is proving useful; it is defining potential gaps in the research that could lead to an excellent dissertation.

My own model of a creative classroom moves students from a state of ignorance about a subject through passive to active to creative levels of engagement. I need to determine if an innovative level may be warranted, and to see in what ways students can become innovators. Some avenues could include students becoming inventors, students as programmers or coders including developing their own computer games, students as makers (I am beginning to study makerspaces as part of my EDF 701-200 class this summer), students as teachers, students as education content creators, students as engineers, and students as scientists. Although there have been some studies in each of these areas, I don’t think anyone has put them together in quite the manner I propose nor looked at them together systematically. This could take years to fully explore.

All of these ideas must be part of a student-centered classroom where much of the work is driven by the students themselves through exploring their own interests. This in turn leads to exploring the nature of student engagement – is it often merely compliance, as Schlechty proposes, or does it come as a synergistic intersection between the task, the student, and the teacher? At what point do students change from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation and become self-directed learners? How does passion and the meaningfulness of the task effect all of this?

A. T. Black with his patented headgates, installed in a canal near our hometown.

We hear about the need to teach the so-called “soft” skills of design thinking, critical thinking, data analysis, problem solving, communication, and collaboration. All of these are part of students learning how to become successful innovators and are essential for a 21st century economy. Much has been written about some, but not all, of these skill areas. I have experience in authentic data usage, but so much more can be done here that a great dissertation could come out of it.

Over all of this, there are questions of theory, pedagogy, and teacher training. If we are to teach students creativity and innovation (and I think we should), then how do we train the teachers how to teach these concepts successfully? What theory supports these ideas, or do new theories need to be developed? What pedagogies and classroom structures, such as project or problem-based learning, will best lead to students developing creativity? What types of organizational changes in schools will be required to implement these ideas? How do we systematically move schools toward teaching creativity and innovation? How are schools and teachers doing it now? How do we reform schools to make our entire society more creative and innovative?

Big questions. The type that are a passion for me and drive me to complete this EdD program. It has already been a challenging year, but except for that one horrible statistics class, my grades have been good and my projects well-thought of, mostly because I have stayed focused on the ideas of this diagram. So much still needs to be researched, and there are many possible studies I can do that arise from these concepts. I have already conducted one initial study with three teammates this winter semester, which I will report on soon. I will be devoting my remaining years as a educator to defining and refining this diagram. In the end, I hope to write a series of popular books, geared toward practicing teachers, on how to promote creativity and innovation in the classroom and in the world. I have about ten years more before I expect my health will force me to retire (if I ever can), so I’d better get cracking.